- Home

- Philip Luker

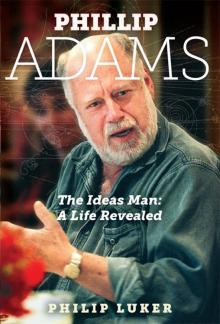

Phillip Adams Page 2

Phillip Adams Read online

Page 2

***

Phillip Adams was born on July 12, 1939, just as the curtains were going up on World War II. He entered the world in Maryborough in central Victoria, where his father Charles was the Congregational minister. Charles and his wife Sylvia lived in a drab little weatherboard manse with a tennis court of buckled asphalt, beside a dull-looking brick church. It was hardly inspiring to young Phillip, let alone to his mother. Nor even to his father — it seemed all members of the Adams family were unhappy with their lives.

Glancing around Adams’ Sydney office, I realise how far he’s come from the little boy whose miserable childhood of neglect, hardship and abuse by a hated stepfather seems drawn from the pages of David Copperfield. I asked him what he remembered of his early life.

‘My earliest memory, aged two, was looking up at the sky, which I thought was on fire, flames everywhere.’ Adams’ eyes wandered off as though he was playing back the scene in his head.

‘I could see the flames through the peppercorn trees,’ he continued, ‘and I remember waddling in fear towards the manse and pulling open a battered flywire door to find my father, who told me not to worry because it was only lightning. My father was a petite, shiny little Englishman who not only polished his shoes frantically but even polished the soles. He had come to Australia aged fifteen after being rejected by his mother, who had worked in vaudeville with Charlie Chaplin as a juggler and seal-trainer.’ Having lived such a colourful life, no wonder his grandmother was disappointed with her boring, somewhat obsessive son.

‘What about your mother?’ I asked.

‘She was extraordinarily pretty. She told me later it upset other women in the church. She was depressed about living off my father’s very low wage. I don’t doubt she would have pushed and shoved him into enlisting in World War II as an army chaplain.’

Once his father was off to war, his mother ‘immediately got a job in the rationing service, which gave her liberation, a chance to meet other men, and a wage. She left me, aged three, with my maternal grandparents, Bill and Maude Smith, who raised me on their little flower farm in East Kew in Melbourne for most of the next ten years.

‘My mother was to me like a fairy in a Disney cartoon. She used to arrive at the farm and take me on bike rides. My father was a strange, distant man, who used to post me coconuts from the war, with my name and address on them — a common thing for fathers serving in the Pacific Islands to do for their children back home. The coconuts were my strongest memory of my father. At times also, Father would come home and be enormously emotional with me, which puzzled me because he was almost a total stranger, as was my mother.

‘I rarely saw either parent and, when I did, it wasn’t really successful. I remember my father, in uniform, arriving at the farm, taking me by the hand and walking me up High Street, East Kew, for my first day at East Kew Primary School. I remember crying all the way and not wanting to be left there. I didn’t understand what my parents were up to or where they were. What I did understand was that I was living with my grandparents on a little flower farm at East Kew.’

***

Bill Smith and his identical twin brother Fred grew flowers commercially on four acres of land that, these days, is covered with faded brick-veneer houses in suburban Melbourne. All that remains of the farm where the brothers grew violets, chrysanthemums and poppies for the Queen Victoria Market is a street name, Violet Grove. The farm had a draught horse, an old plough and an outside toilet. Adams’ grandparents were incredibly poor. Aged four or five, Phillip didn’t realise he was poor until he went to school in handmade clothes and felt humiliated next to his better-dressed schoolmates. Living in a little sleepout at the farm, he lay in his old brass bed wondering whether there was a god and what colour dead would be. He agonised over these questions night after night.

It would not have been surprising for young Phillip to grasp at a comforting fable or to believe in God to give him peace, but he found he couldn’t believe what he was told in religion classes at school. He thought it was nonsense.

‘The important thing about this,’ he told me, ‘was that I had never heard the words “eternity” or “infinity”. I had never read a book and I had no-one to talk to about it. People later assumed it was a reaction against my father’s Christianity. It was nothing to do with that. I hardly ever saw him.’

Adams is well known as an atheist but said he didn’t reject God at this early time of his life. ‘He was never in contention,’ he explained. ‘My objection was that, whenever religious teachers at school told me there had to be a God because there had to be a beginning of everything, and God created everything, I would ask, “And who created God?” I once asked my grandmother and she boxed me on the ear, the only time she ever hit me. I realised I was on to something. It was the most important moment of my life, from which everything else followed.’

To have had such a realisation and lived by it all these years displays a steadfastness usually available only to those raised in the church. ‘Everyone agreed there wasn’t an ending, because they believed they would go to either Heaven or Hell. Equally, to me, it seemed there couldn’t have been a beginning. No end, no beginning, no need for God. I realised life just was, or wasn’t, and didn’t need an explanation. It certainly didn’t need a god, because a god explained nothing. A god simply shoved the questions back.

‘I grew up embarrassed by religion. I couldn’t believe that other people really believed. Any human must feel awe when they look up at the stars or contemplate what it is all about. But I couldn’t believe God created it. In school you go from studying water, what floats or doesn’t float, and then, in religious class, Jesus walks on it. And these days at Late Night Live, I sit down with scientists who claim they can co-exist with Christianity’s funny mythology, written by people who knew nothing about the world and thought the Sun went around the Earth, and who had no vision beyond the horizon, and believed stories about a virgin birth. All these were stories in exactly the same category as stories by Hans Christian Andersen, but not as funny.’

By his own reckoning, the loneliness of being isolated from his parents and living with his grandparents made Phillip an extraordinarily solemn, strange little character. One memory he recounted to me captured his state of mind neatly: ‘My grandfather Bill and his twin Fred had been gold miners in Western Australia and started the flower farm together,’ Adams explained. ‘When Fred died, Bill and Maude sold Fred’s house and it was pulled on a truck up High Street, East Kew, to become the Kew Cemetery caretaker’s house. I can never forget seeing the house moving along the street to the cemetery. It was as if the house was being buried along with Fred.’ For an already melancholic child, this event would seem much more dramatic. Clearly, it has still not lost its resonance with Adams.

***

Those early years on the flower farm have had a lasting impact. While his grandparents made little conscious attempt to educate young Phillip, he nonetheless learned a lot sitting at the kitchen table in his grandparents’ weatherboard house. Their influence can be seen in many of his core values: from his close relationship to the land to his grandfather’s strong, earthy, working-class sense of justice.

‘My grandfather was gruff and distant, with the simplicity of a bushie,’ said Adams. ‘He gave me a sense of physicality. I used to watch him ploughing the fields with his huge draught horse, using the same kind of plough as the Egyptians used thousands of years ago. Off Grandpa would go, the plough bucking through the earth. He would let me stand between him and the plough, in the arch of his arms and with my little hands on the plough. To me, Grandpa was a giant of a man with a giant of a horse. I remember the sense of the physical and the smell of manure. It was a very elemental and simple world. No clock. Grandpa would tell the time by the sun.’

Clearly, though, Bill Smith was more than just a simple bushie. Adams remembers watching and listening as his grandfather propped a copy of The Age up on a sauce bottle and read aloud an article about “The Long Mar

ch” in China, declaring that the poor Chinese deserved a better life.

‘Grandmother was immensely caring. The food at home was incredibly simple, such as mutton kept in an ice chest, dripping on toast and a few vegetables they grew, such as beetroot. The house had electricity but my grandparents were too poor to have even a vacuum cleaner. They had a carpet sweeper. A horse and cart came in summer with ice for the ice chest and in winter with wood for the fire in the hearth. A baker delivered bread.

‘The only electrical gadget they had was a radio, and we listened to the serials and the hit parade. Grandpa had never owned a watch; he had a clock won at cricket, on the mantelpiece, with a big brass key. I thought it was the most wonderful thing in the world and Grandpa promised he would leave it to me when he died. My school friends’ parents had cars, which were still fairly unusual in Australia before television changed everything in 1956. I would sit on the kerb doing what many children did, writing down the numberplates of cars and trams as they passed.’

Adams evokes an Australia that is familiar to many of his generation but, for all the harkening back to ‘simpler times’, it is obvious that his life wasn’t simple. His parents were absent and he was questioning his very reason for being alive.

From the time Phillip could read, his lifelong, desperate need to read developed quickly — he even learned to read The Age upside down across the table from his grandfather. He quite liked Biggles books, and The Billabong Books by Mary Grant Bruce, a series of Australian stories for children. So, despite his physical sense of isolation, he clearly connected to stories and to words. Only he knows how valuable they were to him, then.

Cultural and intellectual life in Kew in the 1950s was pretty typical of the rest of the country and, for young Phillip, consisted of an occasional comic stolen from the local newsagent or swapped with his friends. His favourites were Batman and Superman. Once a week, on Saturday afternoons, he went to the Rialto Cinema in Kew to see Tom and Jerry cartoons, Batman and Robin serials and Tarzan movies starring Johnny Weismuller. A shilling bought a ticket and an ice cream.

Later Phillip’s grandparents took him to the posh Greater Union Cinema, which had American and sometimes English movies but never Australian ones. The only history he learned was American; the only indigenous people he saw were ‘Red Indians’. His entire cultural experience was American. He and his mates even re-enacted Tarzan films in the gumtrees along the Yarra riverbank.

One of those mates was his best friend from school, Johnny Sinclair, who lived in a posh house over the side fence from the Smiths’ farm. Johnny was Catholic, so on their morning walk together to school, Phillip would turn left to the state school and Johnny would turn right to the Catholic school. In Phillip’s eyes, the Catholic school contained stark, frightening, bat-like creatures called nuns, who put the fear of Christ into him whenever he saw them. Phillip would join other boys from the state school chanting, ‘Catholic dogs stink like frogs jumping out of hollow logs’ and Johnny and his schoolmates would chant, ‘State, state, full of hate’.

Adams remembers, ‘We’d scream abuse at Catholics at a time when, at our parents’ instigation, the division between Catholics and Protestants was immense, deep and bitter, and took generations to ebb away.’ Then, at the end of each day, Phillip and Johnny would walk home together and play.

Despite this unusual friendship, Adams had a genuinely rough time at school. There are few places on earth crueller than a playground, and he was bullied because of his poverty and his sombre demeanour and melancholic manner. Put simply: he was different, and his difference made him a target. He was picked on because he wore funny clothes that Grandma had made him. He rode to school on a grotesque, rusty bicycle that an uncle had given him, and was mocked by the other boys who rode new Malvern Star bikes. He never mastered sport and to this day has no interest in it; when it came to team selection at school, he was never picked.

Adams remembers vomiting with fear some mornings, so strongly did he dread going to school, and not only because the other children bullied him. One teacher took a similar delight in tormenting him. By his own account, however, Adams was not entirely innocent and he remains ashamed of the fact that he joined in attacks on ‘refoes’ — refugee children from Europe. ‘We’d pick on them and tell them to go back,’ he said. Phillip’s torment at school was hardly alleviated by his home life. If he hoped to find refuge there, it was not offered.

***

Any illusions that the end of the war might signal the return to a more normal family life were quickly shattered. ‘My mother dumped my father when he came home during the war,’ he said, ‘and my father was thrown out of the Church because he had a drinking problem. I have terrible memories of being dragged around one day by my mother, the next day by my father, and being told I would have to go to court. There, a judge would ask me which of my parents I wanted to live with — a terrible question.

‘My mother told me, “You’re going to choose me,” and my father told me, “You’re going to choose me.” I remember the feeling of desperation. How could a child make such a decision? Children are still being asked that question. The decision was made for me: I stayed with my grandparents until I was nine or ten. But as Grandpa Bill grew old and ill, he and Maude had to sell their farm. To complete the picture of his David Copperfield childhood, Adams described how his grandparents were swindled out of their land by a Uriah Heep-like businessman. ‘A dignified, corrupt estate agent, who converted it into thirty building blocks, sold them to his mates in a fake auction and Bill and Maude were robbed.’

Then Adams made an important discovery. ‘By this time, I had read all the children’s books in the Kew Library branch near the farm and the librarian took me up one step into the adults’ library and gave me John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Reading it made me realise how the weak are pushed around by the strong, as my grandparents had been.’ And as the young Phillip had been by his parents.

The political instinct suddenly came alive in Phillip Adams when Steinbeck’s ideas led him directly to the Australian Communist Party. He found his way to the banks of the Yarra River, where amateur orators used to speak on Sundays, as they did in The Domain in Sydney. On the Yarra bank were the Catholic Evidence girl, the Evangelicals and a screaming, red-haired fellow who went off to become a big player in the British National Front. And there was the Communist Party. Aged fourteen, Phillip began to turn up regularly to listen to their members’ pronouncements. He remembers tugging at a communist speaker’s jacket and asking how he could join the party. The speaker was amazed, not only because Phillip was underage for membership but also because, in those McCarthyite days, no-one asked to join the Communist Party. Nonetheless, a couple of members took Phillip’s name and he was allowed to join.

***

After Phillip’s mother remarried he moved in with her and her new husband, Michael Bourke. Phillip’s grandfather was a proud, dignified and taciturn man, but on the day Phillip left, the boy could see that the older man was trying not to cry. Bill gave Phillip a ten-shilling note.

Phillip thought Michael Bourke looked like Alf Garnett, the mean-spirited bigot of the English comedy Till Death Us Do Part. Michael was, of all things during the war, a furrier, with an office in Bourke Street in the heart of Melbourne. Instead of fighting in the war, he was making money from selling fur coats. But to the ex-wife of a weak church minister, Bourke, with his black Studebaker and his fur coats, was glamorous. Phillip saw him differently.

‘He was a psychopath, the most appalling creature, and for the next five years, my life was hell. Not just for physical abuse: the occasional outbursts of violence were almost cathartic and released tension. It was his mental torture of my mother and me, and it meant I couldn’t sleep. I still remember rushing, in my pyjamas, into my mother’s bedroom to try to protect her from the crazy, arrogant, sick, silly, sad man.

‘On one particularly bad night, my mother and I ran from the apartment, me in my pyjamas and dress

ing gown and my mother in a nightie and dressing gown, and went to the local pictures to hide. You can imagine how embarrassed we were, dressed like that. On the screen appeared a sign: “Mrs Bourke wanted at the manager’s office”. We waited in our seats, hoping Michael would go away, and later went home because we had nowhere else to go. This was long before the days of women’s refuges. In any case, my mother would have been too ashamed and embarrassed to admit that she, as a cotton mill’s personnel officer, had any marriage problems. She was by then earning more than Michael, whose business had collapsed.’

Looking at this highly accomplished man before me, I wondered at the path he had taken. To listen to him talk about his stepfather, it was clear that these memories were strong, perhaps constant. It was almost as if his stepfather’s ghost was at his back, still chasing him down the street. I wondered if anyone who has experienced such a thing ever loses the feeling of terror — do they ever feel they can escape, in either space or time?

‘I remember trying to murder my stepfather when I was about eleven — it was highly ineffective. Michael was shaving with a cut-throat razor. I waited until the razor was at his throat and rushed at him, but it didn’t even nick him. The only good thing about the continued horror was that it made me determined to survive and brought me and my mother much closer together.

‘One day, when I was fourteen, I heard Michael abusing my mother in the bedroom. I rushed in and pushed Michael with such velocity that he flew over the bed into the Venetian blinds, which forever showed the impact.

‘My mother had previously, in case of emergencies, put a change of clothes for me in a little suitcase that Michael used for his Masonic Lodge material. She told me to run away, which I did. I ran down the road towards Montmorency Railway Station, pursued by Michael trying to run me down in his Studebaker. I ran into the bush beside the road and arrived at the station in time to catch a train to the city to go to my father.

Phillip Adams

Phillip Adams